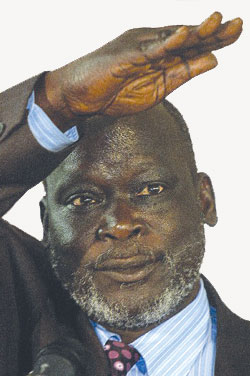

For a long time, we heard much about John Garang de Mabior the politician and the armed rebellion leader. Little have we heard, however, in the conventional Sudanese media sources, about Garang the scholar of Economic Development and the national visionary, or Garang the pan-Africanist. This article attempts to give some glances of the pan-Africanist side of the man (as last week’s article highlighted his vision of economic development and national building).

As a participant in the 17th All African Students’ Conference (AASC) 28th – 29th, May, 2005, which was held in Windhoek, Namibia, Garang contributed a paper that was delivered, on his behalf by Dr. Barnaba Marial Benjamin. Under the theme of ‘Pan-Africanism, African Nationalism and Afro-Arab Relations: Putting the African Nation in Context’, Garang wrote his paper on the case of The Sudan.

In his opening paragraph, Garang directly states: “Africa must unite, not as a continent, but as a Nation, and therein lies our individual and collective survival as a people.” He then refers to the early warning of Kwame Nkrumah, which sadly seemed to have already materialized: “If we do not formulate plans for unity and take active steps to form a political union, we will soon be fighting and warring among ourselves with imperialists and colonialists standing behind the screen pulling various wires, to make us cut each other’s throats for the sake of their diabolical purposes in Africa.” Garang then continues: “This Conference must come up with a credible platform for the consolidation of the economic and political union of Africa, for otherwise all our ad hoc and emergency fire-brigade type efforts will always end up in only managing and restructuring backwardness, poverty, misery and hopelessness without changing them.”

In earlier speeches, to Sudanese audience, Garang confirmed that the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) is unquestionably committed to a united Sudan because it is committed to a united Africa, and further fragmentation of existing African countries (i.e. separatism) is not conducive to continental unity.

African unity is an objective purpose, not a dreamy pursuit. It has clear political and economic benefits, while the opposite option – i.e. fragmentation – has clear political and economic disadvantages. On the economic front, African natural and human resources can be better utilized, for the development of its peoples, under unified management. The richness of African resources lose their significance with fragmentation, and building a big, strong and integrated regional market is key to economic development of all countries. On the political side, the talk is not necessary about creating one big African ‘country’ or something of that sort. The talk is rather about building effective political unity which can facilitate more mobility, of persons and goods, across country borders, and more coherent and consistent systems of governance and legal frameworks that are conducive to the economic and human development of the people of the continent. On the international political arena, the more fragmented the African countries are – economically and politically – the more vulnerable they are in interacting with the rest of the world, especially the world superpowers of our age. World superpowers naturally seek political and economic deals with African nations that work for the benefits of those superpowers, not necessarily of Africans. The bargaining/negotiating powers of Africans can be significantly increased if the same fragmented nations negotiate with the world in a unified voice.

As said, this call for African unity is not merely a sentimental notion, and John Garang is one of the people who understood that. Taking a small look at the European Union is enough to clarify the professed benefits of African unity. Even the strong and stabilized European states understood the great political and economic benefits of continental union, and they acted upon that. The economic and political cooperation between the USA and Canada is also very visible, and the benefits for both countries are evident. Latin American and a number of Asian countries are pushing strongly for more continental unity among themselves. Continental unity is the wave of our age and the foreseen future, and no continent needs it more than Africa does.

Thus, viewing the Sudanese problem from the lens of a pan-Africanist, Garang was a natural unionist who could easily able to see the disadvantages of the fragmentation – i.e. separatist – path, despite all the visible and big challenges of building a truly united Sudanese nation.

But to unite a continent you need to unite a nation, Garang notes. There should be sufficient social coherence among the people of the continent as to allow political and economic unity. Fortunately, Africans in general share historical/cultural commonalities sufficient to make this union work (not without challenges, but with enough reasons to be optimistic). Pan-Africanist scholars of history have cumulated a reliable record that illuminates the historical and cultural shared origins and similarities among the native peoples of Africa. The objective of the pan-Africanist movement is to translate the potential of unity into a living reality.

The Place of Sudan in Africa:

Sudan’s place in African history and present is as important to Sudan as it is to Africa in general. In many ways, Sudan by itself is a microcosm of Africa, in its diversity of people, environments and history; even in its socio-political and economic problems. Garang continues in his paper: “Our country the Sudan is an unfinished product of a long historical process. It has undergone a continuous process of metamorphosis and mutation through history – changing identity, and the correlation of power among the socio-political and socio-historical forces at any given period. The civilizations of Kush, Pharaonic Egypt and the early Christian, Islamic and colonial states have appeared and disappeared on the soil of our great land, the Sudan.

If we visit the corridors of history from the biblical Kush to the present, you will find that the Sudan and the Sudanese have always been there. It is necessary to affirm and for the Sudanese to remind themselves that we are a historical people, because there are persistent and concerted efforts to push us off the rails of history. But there is no book of significance from antiquity in which we are not mentioned and in which our greatness and the richness of our civilization is not narrated… Bluntly put the name “Sudan” or “Bilad El Sud” as the Arabs called it, simply means Africa. To the ancients the names Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan simply meant Africa, an undivided Africa, without internal boundaries.”

He then gives the well-known account of his analysis of the identity crisis sweeping Sudan in this age, and the need for leaning on that historical identity of Sudan to overcome the present cloudy vision that is consuming many living Sudanese citizens.

… and The African Diaspora:

In his paper, Garang does not forget to call for more communication and organization with the African Diaspora, “our African Brothers and Sisters stolen from us centuries ago and now in the Diaspora.” Addressing their concerns, and consolidating the solidarity between continental Africans and Diaspora Africans, is critical for the ‘African renaissance’.

(published in the Citizen Newspaper, Sudan, August 11, 2013)