“A people who free themselves from foreign domination will not be culturally free unless, without underestimating the importance of positive contributions from the oppressor’s culture and other cultures, they return to the upwards paths of their own culture. The latter is nourished by the living reality of the environment and rejects harmful influences as much as any kind of subjection to foreign cultures. We see therefore that, if imperialist domination has the vital need to practice cultural oppression, national liberation is necessarily an act of culture.”

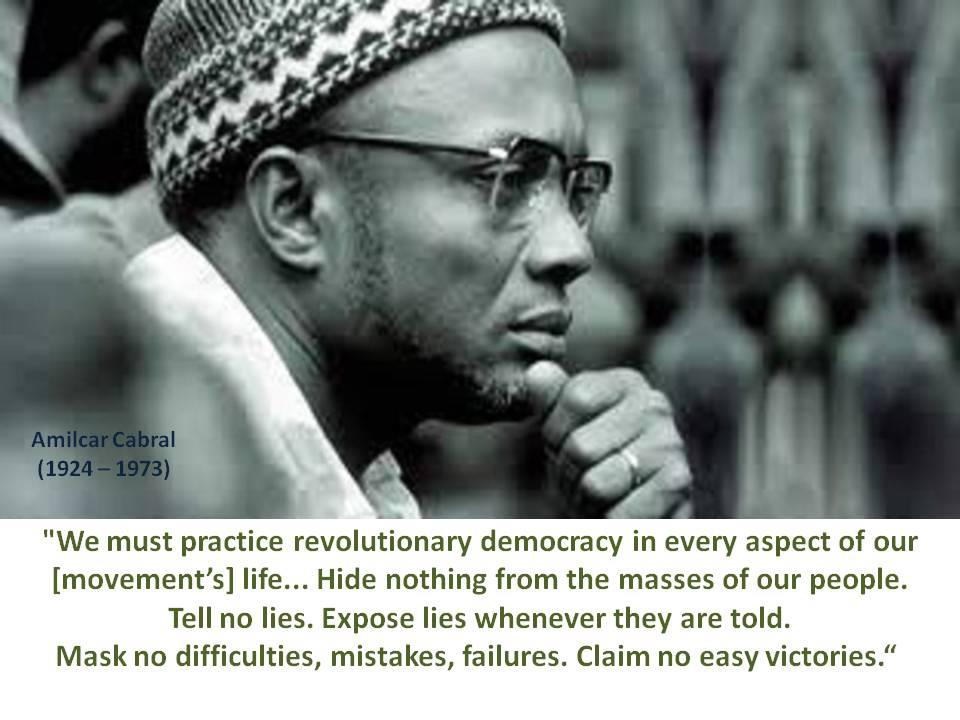

–Amilcar Cabral, 1970

There should be no need to define colonization for any African person today. We know all about that too well. However, we need to talk more about decolonization and national liberation. Decolonization is the process of recuperating from the experience of being colonized. In given historical contexts, it is equal to national liberation. The ‘process’ nature of decolonization says a lot, because when people think of decolonization as an ‘event’ then most will associate it with the declaration of independence and the transfer of political power from a foreign administration to a government of native faces (i.e. “different faces in high places”). This event is NOT decolonization, but maybe one milestone in the process. Decolonization is bigger, deeper, and more complex. This statement is evident from the reality that, often, the foreign colonizer/oppressor is replaced by a native colonizer/oppressor in the eyes of the people.

The cultural front is paramount when it comes to the process of genuine decolonization. The importance of culture shows itself in how the colonizer/oppressor ALWAYS seeks to suppress, distort, and control the authentic cultural expressions of the colonized/oppressed peoples.

Amilcar Cabral (1924-1973), an agricultural engineer by training, national liberation leader by commitment, and a genuine intellectual, dedicated good time and effort to addressing the subject of the role of culture in the decolonization process. Cabral lead one of the few successful national liberation armed struggles in Africa (Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde). He manifested a rare example of a true revolutionary intellectual, leaving behind a legacy of authentic and penetrating theoretical work on issues of national liberation and progressive African perspectives; a legacy given credibility by a parallel legacy of direct action (putting theory into practice—Praxis). It’s quite peculiar and unfortunate how his name and legacy are not well-known to contemporary African generations, at home and in the Diaspora.

In 1970, about 3 years before his assassination, Cabral delivered a speech at Syracuse University, USA, under the name of National Liberation and Culture. In it, he emphasized the central presence of the native culture in resisting external domination: “History teaches us that, in certain circumstances, it is very easy for the foreigner to impose his domination on a people. But it also teaches us that, whatever may be the material aspects of this domination, it can be maintained only by the permanent, organized repression of the cultural life of the people concerned … For, with a strong indigenous cultural life, foreign domination cannot be sure of its perpetuation. At any moment, depending on internal and external factors determining the evolution of the society in question, cultural resistance (indestructible) may take on new forms (political, economic, armed) in order fully to contest foreign domination.”

What makes this insightful observation as important today as it was before, and as relevant to Sudan as it is to Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde, is that ‘foreign domination’ comes in many shapes and forms; sometimes in the guise of groups of fellow citizens with their own agenda of exploitation and monopoly of power and wealth. In fact, the following excerpt from Cabral’s analysis has disturbing familiarity with the current Sudanese situation:

“The ideal situation for foreign rule, whether imperialist or not, would be one of these two alternatives:

– either to practically liquidate the entire population of the dominated country [or region], thus eliminating all possibility of that kind of cultural resistance;

– or to succeed in imposing itself without adversely affecting the culture of the dominated people, that is to say, harmonising the economic and political domination of these people with its cultural personality.The first hypothesis implies the genocide of the indigenous population and, creates a void which takes away from the foreign domination its content and objective: the dominated people. The second hypothesis has not up till now been confirmed by history. Humanity’s great store of experience makes it possible to postulate that it has no practical viability: it is impossible to harmonise economic and political domination of a people whatever the degree of its social development, with the preservation of its culture.With a view to avoiding this alternative-which could be called the dilemma of cultural resistance–colonial imperialist domination has attempted to create theories which, in fact, are nothing but crude racist formulations and express themselves in practice through a permanent siege of the indigenous populations, based on a racist (or democratic) dictatorship.”

Hence, it should not be a mystery why culture is always a target in the eyes of the oppressor. Culture is the tool through which domination is sustained or countered. What follows is that, since foreign domination always needs to use cultural oppression, then decolonization is “necessarily an act of culture,” Cabral concludes.

This conclusion has huge implications. It means nothing less than the immersion of culture into the politics of decolonization and self-determination. Culture is no more relegated simply to folklore, arts and ceremonies, or to proverbs and isolated beliefs (although all of these are important and generally worthy of respect). Culture here becomes a holistic identity, involved in all sociopolitical and socioeconomic endeavors. Culture is thicker than blood. What this also means is that decolonization is not a dry process of structures and legalities, but a MORAL choice and commitment. Furthermore, decolonization is not only a struggle against foreign states, but can many times be against elements of oppression among our own people.

Reading this article with the previous one about the CUSH Manifesto gives a good picture about the critical political role of culture in Sudan.

p.s. while it is generally difficult and to find a comprehensive, agreed-upon, definition of culture, if some folks ask about a concise definition to accompany the argument above, I would recommend Steve Biko’s definition: “A culture is essentially the society’s [authentic and native] composite answer to the varied problems of life. We are experiencing new problems every day, and whatever we do adds to the richness of our cultural heritage.”

(published in the Citizen Newspaper, Sudan, June 9, 2013)