A common, empathetic argument that claims to make sense of why a good number of seemingly benign, literate young minds from middle and upper-middle class households, from different parts of the world, end up sympathizing with fanatic violent Islamic groups, such as ‘the Islamic Khalifate State’ (also called Daesh) and Al-Qaeda, and sometimes becoming recruits for them. The argument can be summarized like this: look to the causes of socioeconomic dispossession and political oppression that these young minds were exposed to, first-hand or second-hand (i.e. by sympathizing with those dispossessed and oppressed). These causes, the argument goes, give explanation – albeit no excuse – to why these new militants, and self-proclaimed jidahis, turn to fanatic perspectives that make a clear and loud break with the international community and its conventions.

A good representation of this argument was articulated by Rob Leech, in The Guardian, 22 October 2014.[i] Rob writes about his stepbrother Richard Dart, from West London, who converted to Islam a few years ago, after which he grew quite militant about his views, influenced by Fanatic Islamist ideologies. Rich grew militant to the point that he was caught in 2013, trying to reach Pakistan to join the Taliban. Before that happened, Rob was also able to meet Rich’s ‘brothers’ who had the same ideological tendencies. In one summarizing passage, Rob says:

“What I saw were, and I hate to say it – vulnerable young men – with massive great chips on their shoulders. With their radical new status they felt empowered, superior and perhaps most annoyingly for me, righteous.

In a former life, the world they had been brought up in had wronged them. Perhaps they had family troubles, or maybe society shunned them, whatever it was, they resented it – they were lost, empty and had no stake in the western world. Becoming a radical Muslim reversed the polarity.

It’s a cliquey club from which everything beyond is viewed as imperfect at best, or evil at worst. And it’s the evils that these guys saturate their perceptions of the world with. Horrific, graphic and brutal images of the suffering, pain and death of Muslims at the hands of the west, played out alongside a powerful narrative of oppression and injustice – a narrative that is difficult to dismantle.”

The argument itself, above, is mostly noble, and not entirely false, one must say–especially when one is about to show their disagreement with it. Yes, I have a problem with expressions about how those turned-self-proclaimed-jihadis are claimed to have been moved by images of oppression of Muslims at the hands of the West. I do not say that this is not true, but I say that whether it is true or not it gives us little understanding of their motives.

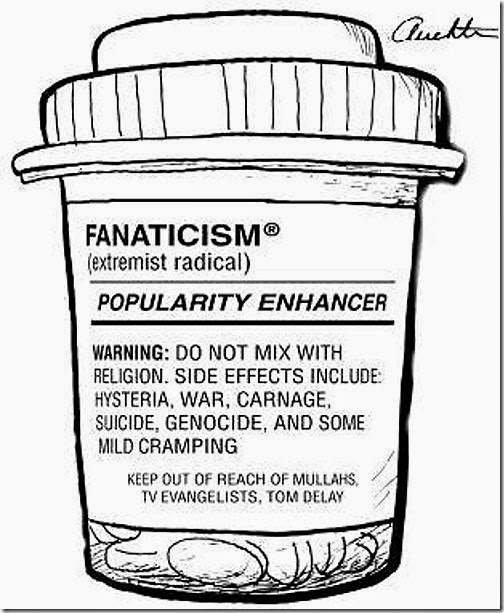

Fanatic ideas finish what confusion starts

Some observations are worthy of mention and reflection: a report by the United Nations Security Council says that there are currently more than 15,000 foreign fighters in Iraq and Syria, from around 80 countries, who are mostly with Daesh.[ii] A good number of those foreign fighters came from financially comfortable families and communities, and have high literacy levels.[iii] Some of them are recent converts to Islam (like Richard Dart), which makes it difficult to speculate that what they had learned in their upbringing had something to do with it. Others among those foreign fighters do not know Arabic enough, and were not able to engage the holy Islamic scriptures directly at any point in their lives. Generally, there is no surprise here and nothing particularly new. Usama bin Laden and Ayman Al-Zawahiri, the two big names of Al-Qaeda, are both good examples of high literacy and a former wealthy lifestyle before becoming the two faces of Islamic fanaticism we now know. Frankly, the phenomenon of wealthy fanatics with high literacy levels exists in all religions. When we look at the numbers and the realities, there is a different picture than what the empathetic argument claims.

Let’s take for example the youth of Afrikan-descent who turn to self-proclaimed-jihadis, why is it that the oppression of ‘Muslims’ in Iraq and the Levant moves them so much that they feel they have to do something about it, but the suffering of their own people in closer proximity to them, and in their own communities – at home and abroad, Muslims and non-Muslims – does not move them in the same way into some sort of radical action?

Let’s all take for example Western converts that are enthusiastic about joining groups like Daesh. They did not identify as Muslims for most of their lives, but the argument above seems to propose that as soon as they convert they start to strongly sympathize with Muslims alone and feel resentment of their own Western societies – their communities and families – to the point that they are ready to carry out acts of extreme violence unlike anything they themselves have ever experienced in their previous, relatively sheltered lives. More irony is when the claim of being moved by sympathy for the oppressed, or by resentment of society for having failed them, renders the more oppressive and violent ‘solutions’ they subscribe to, with which they do not only condone killing, torturing and raping innocent lives, but also participate in such acts.

It is better to call things as evidence provides: this is a result of brainwashing and political indoctrination with fanatic ideas of religious flavor (since not all fanatic ideas are necessarily religious), more than it is the result of emotions of sympathy for the oppressed. These new recruits were successfully brainwashed, because they were prone to. Many of them may have had quite stable lives with good literacy before their ideological transformation, but it is reasonable to conclude that they were not educated enough about the world–about their histories, about how systems of oppression work and why, about class consciousness, about anti-colonialist movements, about civil rights, about being positively engaged in their own communities and about genuine paths of self-realization. I make a clear distinction between ‘literacy’ and ‘education’ at this junction, because it is the latter that is malnourished in this case, not the former. I use ‘literacy’ here to refer not just reading and writing, but to the level of knowledge acquired by accumulating information (document literacy) with probably some specialized trade skills (e.g. computer literacy, medicine literacy, legal literacy, science litaracy, etc.). ‘Education’ on the other hand is when such literacy is combined with critical thinking and connecting to view the world through the new lens that complex knowledge systems and philosophies provide, instead of the narrow lens of fanatic ideologies.

My personal, sad conclusion is: all those who lack qualitative education and conscientization (critical consciousness) are prone to being influenced by fanatic, reductionist, destructive ideologies; Muslim or non-Muslim. They are also prone, in the same way, to being oblivious agents of the present-day systems of oppression, either serving their self-interest or being largely clueless about the impact of their participation in propagating such systems.

Not all ‘extremists’ are the same. Ideology makes a big difference

In one recorded interview with Malcolm X, he was provoked to speak about the ‘extremism’ of his views. His response delivered a very good point home, when he pointed out that the USA itself, as a country, was founded on extremist perspectives. Quoting Patrick Henry’s “Give me liberty or give me death”, Malcolm added, “That is extreme.” Indeed, the leaders of the American Revolutionary war were viewed as extremists and terrorists in the eyes of the British Empire.

History allows us to compare radical militants with each other–those who choose to completely disconnect from the establishment of their times and destroy-to-rebuild (or at least claim to be doing so), i.e. those who the media and authorities like to call ‘terrorists.’

For example, acts of sabotage against the state, and attack on civilian sites (with some civilian casualties) were not only committed by the likes of Daesh and Al-Qaeda. The African National Congress (ANC) of South Africa was once labeled a terrorist organization precisely because of such acts against the Apartheid establishment in South Africa, and Nelson Mandela, the man the West likes to celebrate as a symbol of forgiveness and peaceful resolutions, was actually the first leader of the ANC’s military wing that made the ANC a ‘terrorist’ organization. The SPLM (Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement) attacked oil refineries, and other civilian strategic sites, in its Guerrilla war against the Khartoum regime. The PAIGC (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde) did relatively the same thing against the Portuguese colonialists. In Latin America, the Cuban revolution was started by a group of armed militants who were easily labeled as ‘terrorists’ due to the same tendencies.

However, how are those mentioned above different from the likes of Daesh and Al-Qaeda? It is the very different ideologies they subscribe to. A Daesh militant can kill an innocent civilian for the reason that they follow a religious doctrine deemed ‘heretic’ or ‘infidel’ by the militant group. A Guerrilla fighter from Guinea-Bissau would have not done the same—i.e. the ideological difference between ‘fighting for the people’ and ‘fighting for Allah’ (i.e. the ‘Allah’ which the fanatics shape to their favor).

Being devastated by the oppression and dehumanization we see and experience in the world today has little to do, overall, with resolving to fanatic, reductionist and anti-human convictions. Even when some choose to be armed militants, they have a choice to make as to what kind of armed militants they want to be: an uneducated, dogmatic one, or one with critical consciousness and pro-human vision.

Terrorism vs. Violent Resistance

In a paper titled ‘Beyond Empire and Terror’, Robert Cox of York University (Canada) demonstrated a common critical theorist perspective regarding terrorism, explaining it only in terms of socioeconomic inequality as:

“the weapon of the weaker force confronting military and police power… The word ‘terrorist’ is used by established authority to stress the illegitimacy of the perpetrators of irregular violence. Those people prefer words like ‘freedom fighters’ and ‘martyrs’ that lay claim to an alternative legitimacy.” [iv]

While this view is partly justified in response to how the label ‘terrorist’ is used by established authorities, it is however quite problematic when it comes to addressing ‘terrorism’ in its diversity. Cox generalized certain historical experiences of armed resistance that happened against established authorities and claimed alternative legitimacy, and were subsequently called ‘terrorists’ (similar to the ones I mentioned above), to conclude by essentially implying that all or most of those who are called terrorists by established authorities come together under the same classification. There is error in this message, as those groups should be more analyzed according to their own agenda, ideologies and actions on the ground. Where would the case of the current Sudanese government fit, for example, as a group with the highest ‘legal’ legitimacy in its own territories, but evidently associated with the international net of Islamic terrorism – sheltering Al-Qaeda leaders, training terrorist agents and planning and attempting assassinations of other heads of states?[v]

The many fanatic and violent groups in our world today that claim to represent the only legitimate version of Islam do not have enough legitimacy to act in the name of oppressed Muslims, and they do not even consider that legitimacy a priority. The issue of religious fanaticism is a complicated one that requires cultural and political-economic factors to understand, but not without understanding the role of ideology. Religious fanatics claim authority and legitimacy directly from the divine and for this they do not recognize the authority of ‘people’, even their own people. Their interpretation of what is religiously right and true does not depend on what oppressed people agree upon. They do not speak in the name of the people, but in the name of the divine (in their claim). They do explain their actions sometimes due to the unfairness of the current global situation and powers-that-be, but only to stress that ‘human’ solutions are wrong, and that we must all resolve to the divine teachings they claim monopoly over.

Religion is a powerful motivational vehicle, as it has mostly been throughout history, due to its proven strong influence on our collective and individual human psychology. If we dismiss this self-evident point from our analyses, we do so at our own peril.

For this problem of distinction between the many alleged ‘terrorisms’ I propose the discrimination between terrorism and violent resistance. Terrorism and violent resistance differ greatly in their agenda, ideologies and actions on the ground, which makes it erroneous to treat them as similar concepts. A good number of violent resistance movements have some legitimacy to speak on behalf of the groups they claim to represent, while terrorist movement don’t have that legitimacy. A close example for me, as a Sudanese, is the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A), which was a legitimate violent resistance movement that had initiated armed opposition against the Sudanese central (Khartoum) regimes in the name of the marginalized peoples of Sudan. This movement came to be internationally legitimized after years of fighting with consecutive Khartoum regimes. The SPLM/A accepted, in principle, the means of international diplomacy from early years, besides armed struggle, which is something organizations like Daesh or Al-Qaeda fail to accept, simply because they do not have the legitimate ground that allows them to maneuver within the international community, because their legitimacy is not based on ‘earthly’ grounds of championing the cause of dispossessed and oppressed human beings.

Therefore one can also make the claim that, given the proper conditions, violent resistance movements are more prone to becoming civil socio-political movements, because they capitalize on the support of the peoples they represent, while terrorist groups do not have the capacity, nor the willingness, to become civil movements under any reasonable circumstances, because their aspirations and implementation methods have no ground in civil society. In generalization, violent resistance movements are civil movements that are yet to find the proper conditions to practice their political activities non-violently, while terrorist groups are inherently violent, without the capacity of becoming non-violent–even if they secure dominant power, they will sustain it by violent coercion.

Good Intentions are acknowledged, but…

There is no doubt that the Western and non-Western writers and media spokespersons who adopt the empathetic argument above of the ‘social conditions that make good individuals become religious terrorists’ are acting with better intentions than the other Western writers and media spokespersons who seize the opportunity to paint ALL Muslims with the same brush as Daesh and Al-Qaeda, simply based on the very weak association that ‘they are all Muslims’. The latter group of media representatives is indeed offering ignorant and dangerous media substance. Yet, that does not totally absolve the former group of forgoing analytical depth.

Those who seek to paint almost all Muslims with the same brush face the direct and simple problem that there is no Muslim group out there that currently represents all Muslims; let alone groups such as Daesh and Al-Qaeda with the majority of their victims being other Muslims who disagree with them in belief, opinion and actions.

Yet, we should never undermine the power of human agency and what ideology can do to it; what indoctrination can do to it. The promise of going to paradise in the afterlife, where one can have all the material desires that they wanted to have here on earth, without the hassle and for an unlimited time, may sound quite naïve to most ears, but with some persistence and clever illusions many uneducated – albeit literate – and desperate minds can fall victim to such notion . With enough persuasion of religious fervor, some are actually convinced that if they do horrible things in this life they will be favorably rewarded in the afterlife, because what they did allegedly served God’s will on Earth.

Fanaticism cripples the intellect, and your socioeconomic status does not make you immune to it—critical education does.

(old blog)

—————————————

[i] Robb Leech. “My brother wanted to be a jihadi – and society is creating many more like him.” The Guardian, October 22, 2014: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/oct/22/brother-jihadi-terrorist-society-extremism?CMP=twt_gu

[ii] Spencer Ackerman. “Foreign jihadists flocking to Iraq and Syria on ‘unprecedented scale’ – UN.” The Guardian, October 30, 2014. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/30/foreign-jihadist-iraq-syria-unprecedented-un-isis

[iii] Atika Shubert and Bharati Naik. “CNN exclusive: From Glasgow girl to ‘bedroom radical’ and ISIS bride.” CNN Cable News Network, September 5, 2014: http://edition.cnn.com/2014/09/05/world/europe/isis-bride-glasgow-scotland/

[iv] Robert W. Cox (2004). “Beyond Empire and Terror: Critical Reflections on the Political Economy of World Order.” New Political Economy, Vol. 9, No. 3. [v] Mansour Khalid (2003). War and Peace in Sudan: A tale of two countries. London.